Transcript

EDDIE CONWAY: There’s been a lot of activity in economic development between China and Africa recently, and there’s not enough information about it. I thought I would check with a professor to find out exactly what’s going on. So, joining me today is Dr. Zhiqun Zhu. He’s a professor of political science and international relations at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania. His teaching and research focus on Chinese politics and foreign policy, East Asian political economy and US-China relationships. Thanks for joining me, Dr. Zhu.

ZHIQUN ZHU: It’s my pleasure.

EDDIE CONWAY: Can you just give me an overview of the rise in the relationship economically of China and Africa in general, and what are some of the common misconceptions about that relationship?

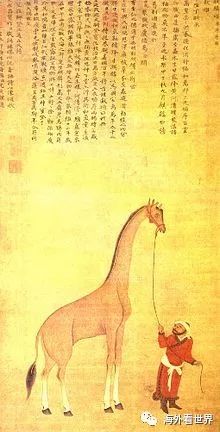

(永乐十二年(公元1415年)从索马里带到中国的长颈鹿。)

ZHIQUN ZHU: Yes…assume that this relationship just got started a couple years ago or five years ago, but of course, China and Africa have a longstanding relationship, going back several hundred years ago. In the Chinese dynasty of 600 years ago, some Chinese merchants actually went to Africa and brought back a giraffe to satisfy the emperor’s curiosity, but contemporary relations between China and Africa really started in the 1950s, right after the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949. In 1956, Egypt actually became the first African country to recognize the new China. In the 1960s and ’70s, when China actually was poorer than many of the African countries, China already started to provide aid and support to many newly independent African countries.

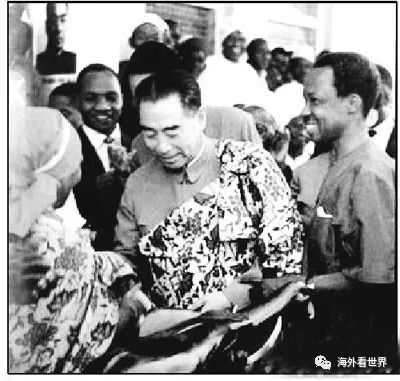

(周总理访问非洲。)

But of course, Africa is far away and poor, so in China’s diplomacy, it has remained a low priority, but in recent decades, especially since the early 1990s, China kind of rediscovered the economic and political strategical values of Africa. That’s why you see this booming relationship between China and Africa. I think that’s the historical background.

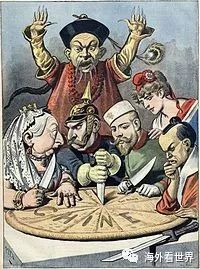

EDDIE CONWAY: How does China’s colonial past spanning several centuries involved with Western powers in the colonial relationship, how does that impact the economic and political relationship of China and Africa today?

ZHIQUN ZHU: That’s a good point. I think as you said, because of China’s own colonial past, it’s very sensitive to these kind of issues. I think that’s why you can see what China’s doing now in Africa is very different from the past colonial powers. I think China’s very sensitive to the charges of being a neo-colonial power or imperial power, terms like exploitation, so China’s activities in Africa typically do not have political conditions attached, and China is really not forcing its way into Africa. It’s not imposing any policies or economic models on Africa. It’s really based on mutual benefits. I think the colonial past of China really is an important factor here. It really shapes how China conducts its business and the economic activities in African countries.

EDDIE CONWAY: As you mentioned previously, there’s been a renewal of that relationship between China and Africa starting maybe in the 1990s. What kind of stuff was China involved in, engaging in Africa after the 1990s?

ZHIQUN ZHU: As you can see, in the 1990s, China’s economy really started to take off, and to provide continued growth for China’s economy. China really needs raw materials, oil and gas, and also it’s also looking for export markets. So, Africa as a whole continent is rich in resources, energy and it’s potentially a huge market. So primarily, I think Africa is particularly important from an economic perspective. That’s why you see massive investment in Africa, trade with all these African countries, but Africa also has political values for China. There are 54 African countries at the United Nations and that’s the largest voting bloc. So, it is politically important for China to form a strong relationship with all these third world developing countries.

There are also military exchanges, starting from the mid 1980s, China dispatched peacekeeping missions to several African countries, like Somalia, Sudan, Congo, and of course the military exchanges also take the form of training military officers of African countries in China. So, the relationship is really taking different forms, not just the economic dimension, but also political, strategic, diplomatic, military and cultural, even educational, I think. The Chinese government has provided hundreds, maybe thousands of government scholarships for African students to study in China.

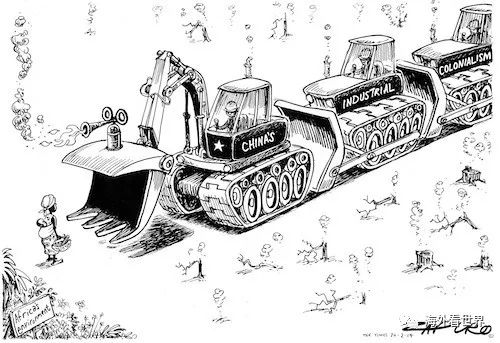

EDDIE CONWAY: Okay. Well, and I understand that China is experimenting with a mixed economy relationship. There’s a capitalist class developing in China. How is those investments in Africa impacting the African worker down on the ground, and is there benefits for the African worker? I understand that a lot, a couple years ago I was in Africa and interacted around what was going on with the Chinese workers and whatnot. It seems like those Chinese companies are bringing their workers and their equipment and their expertise. Is this benefiting the African worker, and if so, in what way?

ZHIQUN ZHU: Yes. I think one of the issues many people are talking about the negative dimensions of China’s investment in Africa is that perhaps China has not helped generate jobs at the local level. As you mentioned, yes, Chinese businesses tend to bring their own workers from China, not really helping the local economies, but I think over the years, especially in the past decade or so, the Chinese government and Chinese businesses have become very sensitive to this issue, and nowadays, yes, they are hiring locally. They are working with local government, NGOs, to make sure that local economies will benefit and local residents will also benefit from the Chinese investment.

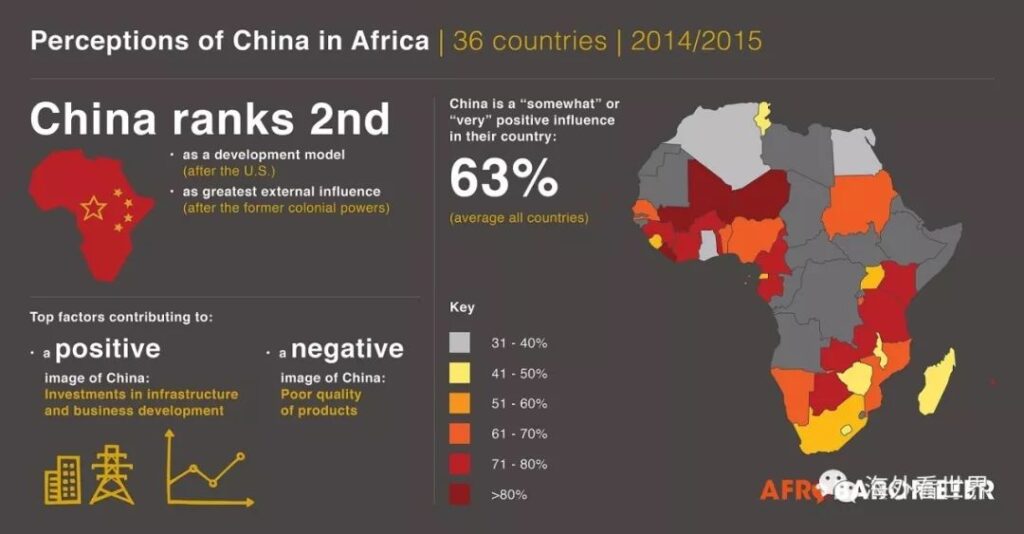

(中国在非洲的形象,数据来自Afrobarometer。)

For example, the recent Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway that was built by China, really in the process actually trying to hire lots of local workers. And right now I think the railway is still managed by Chinese controllers and technicians, but the Chinese side is training local workers so that they can take control of the railway maybe five years after the Chinese contract expires. I think they’ve trained over 15,000 local workers just to manage this railway.

So yes, of course, this is part of globalization. I don’t think one can say that globalization will benefit everybody, so obviously in the process, some people may be left behind. Others may benefit more. But I think that’s an issue that both the Chinese government and the African countries need to work together to make sure that more and more people will benefit from this relationship.