Abstract

This paper will take a closer look at where Japanese foreign policy made three remarkably orientational changes at the historical crossroads of the Meiji restoration in 1868, American occupation in 1945–1952, and in the post-cold war era of the 1990s. During the postcold war era, there arose prolonged policy debates where political elites in Japan reached a consensus of its foreign policy’s new direction, namely a ‘‘middle way’’ mainstream policy. But this ‘‘middle way’’ can be defined as ‘‘tilted,’’ meaning that under different circumstances, different ruling elites would exhibit different tendencies. The policy consensus on this is reflected in some heated internal debates, which have had a profound impact on Japan’s relations with China and the USA.

Keywords

Japanese foreign policy; Tilted middle way; Policy debates; China; The United States.

In the early twenty-first century, Japan’s ruling and opposition parties formed a broad consensus, completing the third major policy choice regarding the country’s foreign policy direction. The fundamental difference between this choice and the first two choices was that, rather than breaking completely with old forms of policy, the incorporation of a middle way became viewed as the best option for Japan’s foreign policy.

In May 2005, Abe Shinzo conducted a luncheon lecture in Washington DC as a warm-up before he became Prime Minister of Japan the next year. At that time, Japan appeared to be strengthening its relations with the USA, while experiencing worsening relations with China and South Korea. During the luncheon, Abe was asked whether these recent developments meant that Japan’s foreign policy was still under the influence of a datsu-a nyu-o, or ‘‘leave Asia, enter Europe,’’ type of policy. He answered that Japan’s relations with the USA and its relationships with Asian neighbors such as China and South Korea were complementary to each other rather than mutually exclusive. Abe’s ideas reflected a new trend in the policy of Japan which attempts to avoid both extremes and instead pursues a path closer to the middle. In essence this could be viewed as a ‘‘follow the middle way’’ strategy. One month after Abe took office, the New York Times also commented that he was taking a ‘‘middle way’’ diplomatic approach (Norimitsu 2006). Japanese Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo, who succeeded Abe in autumn of 2007, was also a politician who implemented a policy based on the middle way. Of Fukuda’s successors, Aso Taro and Hatoyama Yukio, one was of a more conservative nature than the previous two leaders, and the other was more ‘‘liberal.’’ However, it was difficult for either Aso or Hatoyama to diverge far from this middle-way approach.

1 Conceptual Basis

A major change took place in Japan in September 2009 when the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) gained a landslide victory in Japan’s general election, ending the Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) ruling position which began in 1955 (with a short break in 1993), until they came back into power in 2012 under Prime Minister Abe Shinzo. When the DPJ change of guard under Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio, many wondered what impact this change would have on Japan’s foreign relations, until the LDP’s return to power.

(2009年8月,日本民主党鸠山由纪夫与小泽一郎。)

With Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s October 22, 2017, election victory, the LDP’s primacy is secured, for the foreseeable future. In order to better understand the direction of development in Japanese foreign policy, it is necessary to examine Japan’s political mainstream way of thinking. Since Japan developed as a democratic and pluralistic society after World War II, expressions of different views and tendencies within the country are natural. However, simply making a list of different views will not allow one to grasp the true meaning behind Japan’s foreign policy. Therefore, it is necessary to emphasize mainstream thinking, which refers to the dominant preferences within Japan’s political, economic, academic and bureaucratic systems.

(2017年10月,安倍晋三率领日本自民党赢得大选。)

This consensus is reflected in the relative views of the majority, and this relative majority is constantly changing. When analyzing a country’s foreign policy, it is important not to neglect the basic concepts of international relations theory.

Realism emphasizes the strength and fundamental interests of a country (Waltz 1979; Mearsheimer 2001). In terms of this view, leaders pay most attention to how they can maintain the country’s security, prosperity and political power on the international stage. Based on this school of thought, so-called high politics and low politics are placed in a certain order in a country’s foreign policy. In realism, the formulation of political, diplomatic, and military posture is often placed higher than other factors, such as economic and cultural considerations. In this sense, growth and weakening of military and political power among nations, as well as relative changes in the priorities given to national interests, have a significant impact on the country’s foreign-policy making. In other words, realism is based on a consideration of the country’s national strength and fundamental interests. Other factors, such as ideological ones, are placed in a secondary position.

Liberalism, in particular as a result of the recent rise in the field of study devoted to globalization, tends to focus attention on interdependence between nations. Special emphasis is placed upon the strengthening of cooperation and compromise among major powers as a result of increased economic interdependence of nations through enhanced trade (Keohane and Nye 1977). From this point of view, international organizations on the world stage, as well as a series of international institutions aimed at building communities on the regional level, have a profound impact upon inter-state relations and in shaping individual countries’ foreign policies. At the same time, the increasingly popular constructivist theory also provides valuable insight when studying foreign policy issues. As the youngest of the main theories, constructivism views changes in foreign policy by focusing on a country’s policy makers’ perceptions of international situations and regional and world development patterns. Policy makers’ knowledge, position, and feelings about their own country and the history of the region are seen to play an important role in the formulation of foreign policy. From the overview of these schools of thought, it can be seen that liberalist and constructivist emphasize factors other than the strength and interests of countries. Without a doubt, there are many schools of thought in international relations and foreign policy analysis which offer theories that can be used to analyze the trend of Japan’s foreign policy. Those discussed above are only a few of the major ones. Other derivatives have been developed by a number of schools. Examples are power transition theory, interest group theory, and the domestic-international linkage approach, all of which provide very useful theoretical frameworks. In addition, many scholars have recently started trying to analyze international relations theory from the perspective of the Asia–Pacific region (Haggard 2004, 1–38; Ikenberry and Mastanduno 2003). This paper will to some extent utilize some applications of these theories in order to analyze the mainstream thinking of Japanese foreign policy.

2 Literature Review

There are many authors that have written on Japanese politics and foreign policy, specifically, Kenneth Pyle addresses this topic from the ‘‘up and down’’ IR theory perspective, taking a close look at Japan’s power distribution and how it became an economic miracle (Pyle 2007).

(日本历史学家肯尼斯·派尔(Kenneth Pyle)。)

Akira Irie on the other hand views Japanese foreign policy through the lens of cultural international relations (Iriye, 1992).

(日本历史学家入江昭(Akira Irie))

Richard Samuels in his writings on Japanese politics examines how natural disaster had reshaped internal policies (Samuels 2013). Kent Calder (2009) also emphasizes the importance of US–Japan alliance of Japanese foreign policy in his book the Pacific Alliance: Reviving U.S.-Japan Relations. In addition to Japanese politics and foreign policy, there are many works that focus on a China-Japan relations; June Dreyer is one of these scholars and gives a comprehensive breakdown of the power distribution between Japan and China throughout history and modern times and addresses the power transition theory for the region as the countries have changed places as to which is on top (Dreyer 2016). Ming Wan looks at the relational framework between China and Japan through the lens of realism and the military expansions that both Japan and China have exercised over the years. The impact of history is also key to understanding policy: events such as the Nanjing Massacre and its impact on Sino-Japanese relations has been thoroughly documented by both Iris Chang (1997) and Katsuichi Honda (1998); many other authors also address conflict escalators between the two countries of China and Japan such as Junichiro Koizumi’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine.

(日本前首相小泉纯一郎参拜靖国神社。)

All the early works and discussion of Japanese politics, foreign policy, and the impact of history are comprehensive and important, but there are three limitations. First, many of these works are descriptive literatures without deep conceptualization. Second, most of the works on Japanese foreign policy directions are based on a view of realism and often overlook other important elements in the policy making process (except the work of Sheila Smith). The third limitation is that some arguments are outdated and do not reflect new developments of the post-cold war era. My framework of ‘‘tilted middle way’’ foreign policy direction is trying to fill these holes.

3 Historical Review

In the course of its evolution, modern Japanese foreign policy encountered three crossroads at which a significant choice concerning the direction of policy was necessary. The first crossroad occurred in the mid-nineteenth century. When China’s Qing government was invaded by the British-led Western imperialist powers, Japan, as a longtime student of China, paid close attention to what John King Fairbank called ‘‘the clash of the Eastern and Western civilizations’’ and the fall of the Qing Empire. When China was defeated in the Opium War and signed The Treaty of Nanking in 1842, and then suffered humiliation and further loss of sovereign rights from the ensuing invasion of other imperialist countries (such as France, Germany and Russia) with territorial and monetary claims, Japan’s rulers, upper classes and intellectuals watched intently.

(第一个不平等条约1842年《南京条约》签订仪式。)

These events left Japan’s elite with many questions. How could Japan learn from China’s defeat and fall? In which direction should its foreign policy head? Should it continue to adhere to its closed-door and xenophobic policies or thoroughly reform itself and start down a different path?

(日本佩里黑船事件版画。)

The events surrounding China, and Japan’s ensuing questions, formed the background of the 1868 Meiji Restoration in Japan. This reformation led to a major transformation in domestic and foreign affairs. The Meiji Restoration led to Japan’s rapid realization of industrialization; its substantial increase in national strength, and to its rapidly emerging international status. At the end of the nineteenth and in the beginning of the twentieth century, Japan defeated the two great powers in the region. It first overpowered the Qing Empire in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, and it then defeated the Russian Empire in the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. These victories caused Japan’s reputation to grow from that of a small isolated island in the East China Sea into the ‘‘Empire of Imperialist Japan.’’

(1894-1895年中日甲午战争。)

Japan’s political environment, economy, and society also experienced major changes during this period. The nation changed its style and moved from being a predominantly closed feudal and agrarian-based country into being an industrialization-oriented economic and military power. These sudden changes inflated the ego of Japan’s rulers and encouraged them to accept a ‘‘law of the jungle’’-type of logic emphasized by Western colonialists. Thus, beginning in the first half of the twentieth century, Japan began a gradual movement toward militarism.

(1904-1905年日俄战争。)

Japan’s militaristic behavior included colonization of the Korean Peninsula, invasion of northeast China and establishment of the Manchukuo. It also took part in the Germany–Italy–Japan axis, leading to the start of World War II. It invaded Southeast Asia and attacked Pearl Harbor. Japan pursued these actions with the goal of extending the territory of the ‘‘Empire of Imperialist Japan’’ to the largest ever in its history (Chang 1997; Fogel 2000). The dazzling victories, however, were soon followed by painful defeat. In China, Korea, and other Asian countries, Japan was struck by the region’s anti-war campaign.

(原子弹轰炸过后的广岛长崎。)

The USA counter-attacked the Pacific Islands and bombed the Japanese mainland, destroying Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs. The Soviet Red Army marched into northeast China and defeated the Japanese Kwantung Army as well. The combination of these defeats dealt Japan a devastating blow and eventually forced it to surrender and accept US occupation in August 1945. At the end of World War II, a defeated Japan was faced with a second decisive choice in its modern history. In which direction should Japan’s foreign and domestic policy head now? How would Japan be able to redevelop from the ruins of war and return to the international community? How should Japan handle its relations with Asian neighbors, particularly China? These questions pointed to key issues for which Japan needed urgent solutions.

(日本战后经济。)

Under the leadership of the US occupation authorities, Japan adopted its second constitution in 1947, moving down a road peaceful development (Dower 1999). As early as the 1950s, Japan began to enter a period of rapid economic development and became the leader of Asia’s economic takeoff.

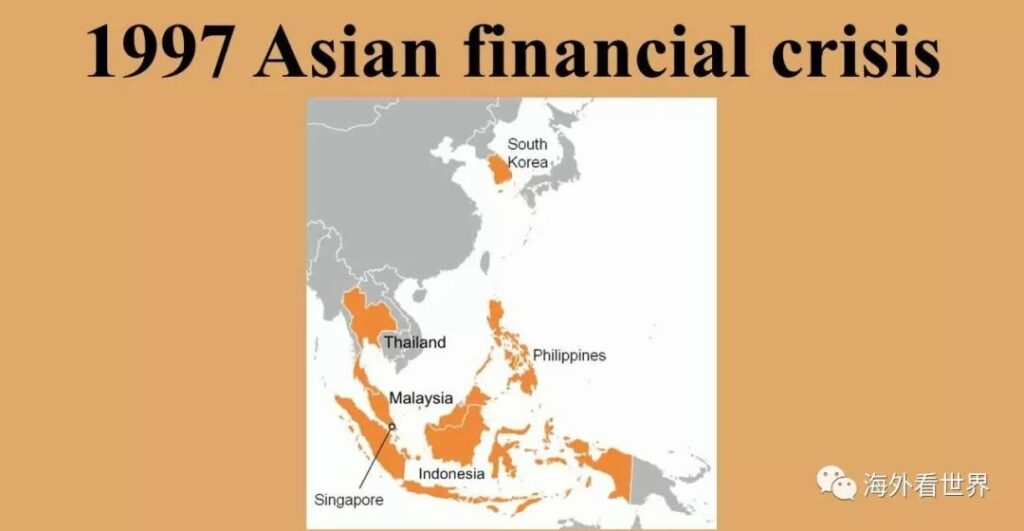

Subsequently, the Japanese economy then overtook those of several European powers and it became the world’s second largest economy, drawing near that of the USA. Japan’s relations with China during this period were heavily influenced, if not determined, by the USA and subsequent developments of the Cold War. China’s rise began with its rapid economic growth in the early 1980s, leading to new international concern regarding the country’s growth. The disintegration of the former Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s, as well as the strengthening of globalization and regionalism, left Japan with an additional series of challenges. From this period until the beginning of this century, Japan also experienced a ‘‘lost decade,’’ which was made even worse by the plight caused by the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

(亚洲金融危机。)

In addition, a nuclear crisis with North Korea also added to these factors, increasing Japan’s sensitivity toward foreign affairs. This series of developments in major domestic and international political and economic issues encouraged a new wave of nationalistic sentiment within the Japanese government and among its public. Politically conservative trends deepened further (Matthews 2003, 158–72). Japanese politicians and political leaders also went through an unprecedented social and political change represented by Prime Minister Koizumi (Calder 2005, 46–9).

(小泉纯一郎。)

All of this brought Japan’s foreign policy to a new crossroads, (Hook et al. 2005) and prompted Japan’s decision makers, politicians and intellectuals at the beginning of this century to start a policy debate on how best to attend to the nation’s concerns and interests within the new global environment (Kawashima 2003). Based on the above discussion, it can be concluded that Japan’s foreign policy experienced three major crossroads during the 100-plus years of challenges and choices that arose in its most recent history. Each one of these policy choices was not only extremely influential in Japan’s own development, but also had significant impacts in Asia and the world. The policy options also were all closely linked with a mainstream type of thinking heavily influenced by realism and idealism. At the time of the first two crossroads, Japan was under tremendous pressure both at home and abroad, and its decisions led to major turning points in history. For example, during the Meiji Restoration, Japan chose to move away from Asia and draw closer to Europe. That is to say, the Japanese decided to distance themselves from the ‘‘backwardness and poverty of East Asia’’, by following strategies of datsu-a nyu-o, or ‘‘leave Asia, enter Europe’’ and fukoku kyohei, meaning ‘‘rich country, strong military’’ in order to catch up with European and American powers. Japan shifted once again however, after World War II when, under the occupation of the USA, it moved from a militarist, authoritarian regime to a democratic, peace-oriented government.

4 Policy Debates and the Tilted Middle Way

In Japan, while there are certainly groups who take extreme stances on foreign policy, they are far from being in the majority. The majority of elite politicians tend to prefer avoiding extremes and instead opt for the middle ground. Even so, different politicians at different times can have different preferences. For this reason, understanding this tendency is the key factor for unraveling the current direction of Japan’s foreign policy. This is what is emphasized in this article as the tilted middle way. Below is an issue-by-issue analysis regarding this type of policy framework.

4.1 Middle Way Number I:

Datsu-a nyu-o Versus Ajia wa hitotsu

During most of Japan’s 2000-year history, its position toward the East Asian region has been clear. However, this came into question in the mid-nineteenth century as Japan’s society faced new challenges. The Japanese

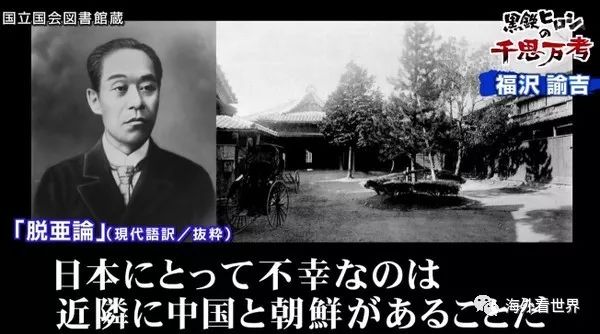

intellectual leader Fukuzawa Yukichi, who established Keio University in Japan, suggested a new policy of datsua nyu-o (leave Asia, enter Europe) (Fukuzawa 2002).

(福泽谕吉。)

Fukuzawa believed that Japan should leave China, which was still considered to be in a backwards state, along with other Asian societies, and follow the example of European powers in order to become a modernized nation. He argued Japan should carry out a series of political and economic reforms and accelerate its modernization. In addition, he called for Japan to form an alliance with the advanced Western countries.

(冈仓天心。)

Another Japanese thinker, Okakura Tenshin, although strongly influenced by Western culture like Fukuzawa, put forward a set of rather different ideas and slogans. In his book Oriental Awakening, he recommended that Japan adopt the idea Ajia wa hitotsu, meaning ‘‘Asia is one.’’ Although Okakura emphasized Japan’s leadership role, he sharply criticized the invasion of the East by Western powers and stressed the importance of standing up against such intrusion by creating a social solidarity in East Asia (Okakura 1940). The huge differences between Okakura’s idea of ‘‘Asia is one’’ and the concept of an East Asian community in contrast to Fukuzawa’s push for greater Westernization represents the dichotomy of ideas among Japanese intellectuals at the time concerning Japan’s position in the international community.

(明治维新时代日本风貌明信片。)

As a result of Japan’s rapidly changing domestic and international situation, including the series of humiliating defeats of the Qing Empire, Fukuzawa’s school of thought gradually became the dominant voice in both the academic and the political world. As the notion of needing to separate from Asia and join Europe became stronger, the trend of respecting and loving Chinese culture was replaced by a mentality of disgust toward Japan’s Asian neighbors. In this sense, the Japanese government’s actions began to represent thinking that ‘‘since the Western powers were able to invade and colonize developing countries, especially in Asia, why shouldn’t Japan do the same?’’

(福泽谕吉“脱亚入欧”。)

This mentality led directly to a series of acts of aggression including the Japanese colonization of the Korean peninsula, its occupation of China and invasion of several Southeast Asian countries. This line of thought went along well with Japan’s expansion policy and did not end until the nation’s defeat in World War II.

(1945年9月,美军上将麦克阿瑟与日本天皇裕仁。)

As mentioned earlier, Japan’s defeat in 1945 led to its second major foreign policy choice in contemporary history. During the 7 years of US occupation, Japan was unable to conduct independent policy choices. Instead, it could only accept the leadership of the USA, taking part in the US-led Western camp. The surrounding international environment also confirmed Japan’s position of having a foreign policy closer to that of the West than to that of the East. The San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1952 and the Japan–US Security Treaty which followed, made Japan a firm member of the Western alliance during the Cold War (Cha 1999). A high degree of Westernization (that is, Americanization) in Japanese society since the end of World War II became a main theme of development.

(2014年4月,美日联合发表声明称钓鱼岛问题适用《日本安保条约》。)

In the years after World War II, the rapid development and economic recovery of Asia brought about the miracles of the ‘‘four little dragons,’’ (South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan) and also forced Japan to recognize the importance of Asia. This awareness has been strengthened by the rapid economic development of China since the early 1980s, as well as the start of a post Cold War East Asian Economic Community. One example is that of “ASEAN+3”, in which China, Japan and South Korea participate together with ASEAN in regional affairs. The Japanese Prime Minister, Abe Shinzo, declared more than once that Japan’s previous policy of datsu-a nyuo was no longer a policy option Japan should follow, indicating that Japan is not only a member of the advanced Western world, but also a part of the East Asian community.

However, in reality, Japanese policy makers—especially when forced to make major policy choices—still tend to lean toward the direction of Europe and the USA. For example, during the second half of Prime Minister Koizumi’s term, when he was asked to respond to the deterioration of Japan–China and Japan–South Korea relations, he replied ‘‘as long as good relations with the USA are maintained, relations with China and South Korea will naturally improve.’’ Koizumi’s mentality of relying heavily on alliances with Europe and America, instead of focusing on improving relations with East Asia was revealed clearly here.

(2003年5月22日,时任日本首相小泉纯一郎与时任美国总统小布什在布什位于德克萨斯的私人农场见面,商谈向朝鲜施压的事宜。)

Of course, there were voices in Japanese society during this time urging for better relations with China, Korea and other Asian countries. Concern was particularly strong in the business community, which was worried about the economy in Asia and Japan’s weakened economic status and urged Japan’s leaders to ‘‘return to Asia.’’ This is one of the reasons why Abe, after being elected Prime Minister of Japan, made his first foreign visit to China and South Korea in October 2006. Fukuda’s series of policies to strengthen cooperation between Japan and China and Japan and South Korea also provides further evidence of this shift.

(2015年8月13日日本前首相鸠山由纪夫在韩国首尔朝鲜日治时期的西大门刑务所纪念馆前下跪忏悔)

Japan’s Prime Minister Hatoyama, 2009–2010, went even further by advocating that instead of datsu-a nyu-o, Japan should move toward Ajia wa hitotsu, meaning moving away from Europe and returning to Asia (Guo 2009). Right before his official inauguration, Hatoyama published an op-ed in The New York Times entitled ‘‘A New Path for Japan’’ discussing Japan’s national goals and strategy. He stated, ‘‘of course, the Japan–USA security pact will continue to be the cornerstone of Japanese diplomatic policy.’’ Then he emphasized, ‘‘but at the same time we must not forget our identity as a nation located in Asia’’ (Yukio 2009). One can tell that the prime minister might have been tilted toward Asia but could not move away from Japan’s alliance with the USA. This middle-way approach in which the Japan–US alliance remains the base axis, while emphasis is placed on good relations with Asian countries, is likely to continue as the most dominant theme of Japanese foreign policy for the foreseeable future.

4.2 Middle Way Number II:

Peace Versus Armaments

The direction of Japan’s path of national development was the subject of several major policy debates during the Meiji Restoration. The consensus reached by the Japanese leadership and intellectuals was to follow a policy of fukoku kyohei, or ‘‘rich country, strong military.’’ In other words, it was believed that in order to realize its goal of reaching political power equal to that of Western countries, Japan needed to industrialize and become a military power. In this sense, both economic and military developments were viewed as equally important. From the latter half of the nineteenth century until World War II, military development was the base of Japan’s diplomatic priorities. However, following its crushing defeat in World War II, and under the leadership of the USA, both the ruling and opposition parties in Japan decided to learn from their mistakes and adopted a new constitution in 1947 based on peace. Article IX of the constitution, known as the ‘‘Peace Clause,’’ formally renounces any military engagement except in self-defense.

(日本1947年宪法第9条,“和平条款”)

This clause has laid the foundation for Japan’s peace and development for more than half a century. Immediately after the occupation, the USA signed a security treaty with Japan in which it pledged to provide a nuclear umbrella of protection. Thus, in spite of facing security threats from the former Soviet Union during the Cold War, Japan was able to dedicate its energy toward developing its economy rather than its military, with its military budget hovering around only one percent of its GDP. This later became known as a ‘‘free ride’’ strategy for economic development. This agreement also laid down the guidelines for Japan’s foreign policy, which set economic development as the country’s top priority (Heginbotham and Samuels 1998, 171–203). As Japan’s national strength grew, questions began to be raised as to whether the country should also start enhancing its military status or whether it should focus on becoming a military power (Hu 2004, 24–38).

(2017年各国军费预算占各国GDP比例。)

The concept of an ‘‘ordinary country’’ suggested by veteran Japanese Politician Ozawa Ichiro was a representation of this trend (Inoguchi and Bacon 2006, 1–21). The push for this concept came after the USA initiated the first Iraq War. Japan provided enormous economic support for the effort. However, after the war, Japan’s name was left out of a letter of thanks published by the Kuwaiti government in the New York Times. Kuwait only expressed gratitude in the letter toward a dozen countries that actually sent troops to the country. This was considered a failure of Japan’s ‘‘checkbook diplomacy.’’ A new trend of thought appeared which argued for the need to revise Article IX of the constitution.

Many scholars and politicians began to intensify their efforts to obtain public support for the manufacturing of national armaments, leading to the transformation of Japan’s Defense Agency into the Ministry of Defense. In addition, the subsequent popularity of the ‘‘China threat theory’’ as well as the North Korean nuclear crisis helped promote further support for the movement toward rearmament.

(提出日本应当“正常化”的小泽一郎)

Of course, it should also be noted that the social forces in Japan which adhere to the ideal of peaceful development of society and oppose any build-up of military equipment or strengthening of military power have also had a powerful influence. Japan’s ruling and opposition parties have a large number of politicians and scholars who oppose amending the constitution, particularly Article XI. In their view, Japan’s post-World War II strategy of prioritizing economic development and avoiding military power has been successful. Japan’s peace constitution is unique in the world and has made a significant contribution toward the maintenance of world peace; therefore, Japan should not start back down the road toward militarism. In the heated debate about whether Japan should adhere to its strategy of peaceful development or switch toward a ‘‘normalization’’ of its status in the world by rearming, international public opinion has also been divided.

Mainstream politicians in the USA hope that Japan can become a responsible ‘‘normal’’ country and make its contribution toward international security and world affairs (Rozman 2002, 72–91). In their view, Japan’s post-war development created a solid foundation for a path of peace, making it impossible for Japan to initiate aggression again or pose a security threat to other countries (Green 2006).

On this issue, China, the two Koreas and a few Southeast Asian countries which were invaded by Japan, hold an opposing stance. They believe Japan should adhere strictly to its constitutional restrictions, especially Article IX. They feel Japan should stick to its road of peaceful development and reflect and examine its past crimes of aggression in order to avoid retaking the old road to militarism. In this sense, Japan is not only facing its own dilemma, but also dealing with the two different opinions—that of the USA and that of Asia. In such an environment, Japan’s choice of a middle way is unavoidable. However, for each specific policy, such as the issue of amending the constitution, different political leaders have had different policy preferences.

4.3 Middle Way Number III:

Economic Power Versus Political Power

The first guiding principle for Japanese foreign policy after World War II was the so-called ‘‘Yoshida Doctrine.’’ At that time, Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru put forward economic development as the nation’s top policy priority. As mentioned previously, Japan revised its principle of fukoku kyohei, which had been stressed since the Meiji Restoration. Rich Country was now the primary objective, while the issue of strong military emphasized dependence on the US’s nuclear umbrella. In other words, as long as the Japan–US security treaty guaranteed Japan’s national security, Japan would not need to provide substantial financial resources toward security. Instead, it only needed to maintain a small but strong self-defense force. Over the years, Japan has managed to keep its military expenditure at around one percent of its GDP while still being able to satisfy its need for national defense.

The nationwide efforts to develop the economy helped Japan quickly surpass Great Britain, France, Germany, and other European great powers, and become the second largest economic entity in the world by the 1970s until 2010. Japan’s economic position as a major power was also strengthened by its active economic involvement overseas. Japan’s substantial investment and acquisition of assets in the USA, coupled with the trade frictions between the two countries, caused the world to recognize Japan’s strength, thereby effectively improving Japan’s status as a great power.

(日本ODA。)

In the 1980s, Japan became the largest provider of official development assistance (ODA) to developing countries. Japan held this leading position until its economy took a downturn in the late 1990s and the gap with the USA enlarged. However, even though Japan experienced a ‘‘lost decade’’ of economic downturn, Japan had the second largest economy in the world, until 2010. Its machinery, automobile manufacturing, and electronic high-tech sectors all maintained a leading position in the world (Colignon and Usui 2003; Gao 2001; Vogel 2006).

While Japan’s economic achievements have been huge, its political influence in the world did not corresponded with its level of monetary growth. Japan has faced the dilemma—similar to the peace versus rearming dilemma mentioned in the previous sections—of how to raise its political status to a level that matches its economic status (Wang 2004b, 24–7). Many Japanese politicians have been dissatisfied with Japan’s status as a so-called economic giant but political dwarf. In order to change this, Japan has strengthened its activities in regional affairs, focusing especially on the start-up and development of an East Asian community, and increased regional economic integration by injecting enormous financial resources and energy to spur growth (Katzenstein and Shiraishi 2004). China’s surpassing Japan’s economy in 2010 has further complicated the issue. So, what are Japan’s next foreign policy steps?

(中日GDP对比。)

So far, Japanese citizens have difficulty accepting the truth that Japan is no longer the world’s second largest economy. This has strengthened feelings of insecurity in the domestic populace and indirectly increased support for improving Japan’s defense system (especially during Abe’s term). When analyzing the direction of recent Japanese diplomacies, it is not hard to see how Abe’s administration handles Japan’s multilateral relations with its neighbors.

(2002年9月17日,时任日本首相小泉纯一郎访问平壤,会见时任朝鲜最高领导人金正日。)

Furthermore, Japan’s reluctance to adequately handle the historical problems it still has with other countries has made it difficult for the country to develop a more assertive and influential role in the Asia Pacific region. During the Koizumi administration, Sino-Japanese and Korea–Japan relations worsened because of Koizumi’s successive visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. The decision makers in Tokyo learned that simply emphasizing economic relations or providing financial assistance was not necessarily going to strengthen the nation’s political position or improve diplomatic relations. One example of such misjudgment involves Japan’s use of ODA to China, which it started in 1979. Over a twenty-some-year period, China accepted multi-billions of dollars of economic assistance, including long-term, low-interest loans, grant assistance, and technical assistance (Inada 2002, 121–396; Xide 2000). However, upon entering the twenty-first century, Japan began reducing and freezing aid to China for many reasons (such as the opaqueness of the Chinese military), before finally ending its assistance to China altogether in 2008, when China hosted the Olympic Games. So, while Japan’s overall aid to China played a valuable role in China’s modernization and development, Japan’s sudden cessation of the ODA severely weakened its effect on bilateral political relations. (Tsukasa 2005, 439–61). These were all lessons worth learning by the Japanese government.

(日本对中国的发展援助款,单位:百万美元。)

Another way for Japan to achieve its goal of building up its political power is through existing international organizations. One of the best examples in this regard is Japan’s use of the United Nations as the base axis of its foreign policy for carrying out a series of activities. Japan has also advocated a restructuring of the United Nations Security Council by petitioning to join the USA, Russia, Britain, France and China as a permanent member (Kitaoka 2005, 3–10).

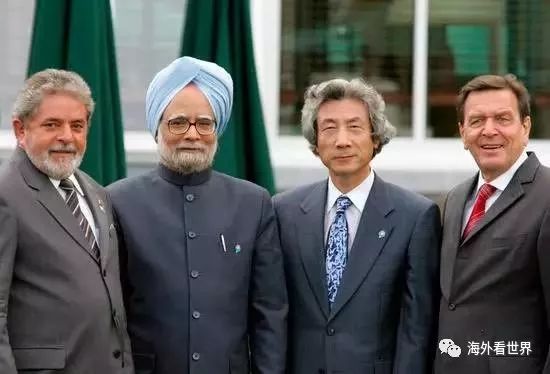

(2005年,日本、德国、印度、巴西四国联合申请成为联合国安理会常任国)

In 2005, Japan, Germany, Brazil and India formed an alliance and launched a full campaign to become permanent members of the UN Security Council. However, Japan was unsuccessful in gathering support from some major powers as well as from its Asian neighbors (Drifte 1999). In the foreseeable future, however, Japan will not abandon its attempt to obtain a permanent seat in the UN Security Council. It will continue to try to get the support of the big powers as well as that of Asian, African and Latin American countries (Mao 2008a, 2008b, 22–3). However, whether Japan will become a permanent member in the near future is still uncertain. In fact, despite the push by domestic mainstream politicians and other elites of the Japanese government to attain political power, there are also voices insisting that Japan should instead focus more maintaining its status as a middle power (Soeya 2008, 36–41). Some believe that it would be more beneficial for Japan to continue prioritizing the ‘‘economy first’’ policy, which was established after World War II and to focus on economic development and democratic issues with the goal of creating a more peaceful and healthy country, rather than competing for a leading role among political and military powers, This view has become the base on which public support for a middle-way approach to foreign policy has been established.

4.4 Middle Way Number IV:

The Leader or The Follower Versus The Partner

In response to a reporter’s question regarding Japan’s future direction in foreign policy, Harvard political scientist Samuel P. Huntington stated, ‘‘I think at this stage, Japan will still follow the USA, but eventually shift toward China.’’ He explained his reasoning by noting that historically, the Japanese have always allied with the world’s number-one power: first with the UK; then with Germany, and finally with the USA. Therefore, Huntington believes that if China becomes a leading power in East Asia, Japan will work to form a possible alliance with China.

(2018年7月,日本与欧盟签署经济伙伴关系协议。)

Rather than attempt to make assertions as to whether or not Huntington’s prediction is correct, it is more beneficial to instead note the psychological factor present in Japanese foreign policy. That is to say, Japan has long had a mentality of befriending the powerful and despising the weak. In this sense, Japan is accustomed to being either a type of big-power follower, or a leader of the neighboring countries, and is not accustomed to dealing with other countries equally. These aspects are quite obvious in terms of Japan’s relations with China. For a couple of 1000 years, Japan regarded Chinese culture as its mother culture and always looked up to it for advice on how best to deal with not only domestic issues but also international affairs. However, after China was invaded and divided by Western powers and became weaker (even being regarded as the ‘‘sick man of East Asia,’’) Japan’s attitude toward China shifted from looking up to looking down on China. It no longer wanted to associate with the Chinese, and instead emphasized a policy of datsu-a nyu-o. Such changes in the relative level of strength between Japan and China have had, and continue to have, a profound impact on Japanese people’s mentality even now. Japan is rather proficient in dealing with the two kinds of relationship, namely ‘‘weak versus strong’’ and ‘‘strong versus weak.’’ However, with the rise of China in East Asia, a new structure of ‘‘strong versus strong’’ has emerged, which troubles Japan tremendously.

Clearly, Tokyo needs to change its mentality in order to better adjust to the transformation of international relations and to adjust psychologically to prepare for the rise of China and the consequential changes in the international order. There is no lack of a pragmatic tradition in both China and Japan. As Wang Gungwu suggested, ‘‘The pragmatic lessons of history run through Chinese and Japanese history: ‘the victor is king, the defeated is but a bandit’’’ (Wang 2004a, 107). Such a psychological change can lead to unprecedented adaptation and development of more partnership relations in Japanese foreign policy. This idea of a middle way therefore offers a vision for Japan’s strategic partnership with China, in which both countries can concentrate on mutually beneficial relations.

4.5 Middle Way Number V:

Traditional Politics Versus Open Public Policy

Any country’s foreign policy is deeply influenced by its domestic politics and the impact of its traditional foreign policy. Japanese Policymaking, a book published in 1993, (Zhao 1993) emphasizes the importance of traditional Japanese foreign policy, offering an analysis of Japanese politics through an informal mechanism. Based on this analytical framework, while the effect of formal mechanisms such as government departments, politicians, and the ruling parties play an important role in the formation of Japanese foreign policy, policy formation is also greatly influenced by traditional politics. These policy-making mechanisms, including tsukiai (social networks) on the societal level; kuromaku (informal institutions and politicians) on the institutional level; and nemawashi (behindthe-scene consensus building) on the individual level, are collectively referred to as non-formal mechanisms. The frequently heard ryotei seiji (restaurant politics) and ‘‘secret envoy diplomacy’’ in Japanese political life are concrete manifestations of such decision-making styles (Blaker, Giarra and Vogel 2002). These informal mechanisms in Japanese foreign policy played an important role during the 1970s in Japan’s diplomacy toward China.

(日本传统政治非正式渠道。)

The increased development of globalization since then has seen Japan undergo noticeable political changes. Japan’s public and politicians now put more emphasis on such factors as democratic values. The transparency of the decision-making process in respect of Japan’s diplomatic policy has increased substantially and public debate has become more prevalent. The power of the public to influence policy making has also obviously increased (Krauss 2000). Both Japan’s ruling and opposition parties have changed their style to a more open and transparent one in order to adapt together with the changes occurring in Japanese society (Schwartz and Pharr 2004). The reforms stemming from major policies Koizumi instituted during his 5-year period in office are good examples of such a change. The open debate of public policies, including that of foreign policy, in addition to an increased use of formal mechanisms, is likely to weaken the effects of ‘‘secret envoys’’ and ‘‘restaurant politics.’’ Japan’s foreign policy will also be more influenced by the context of domestic public opinion, with the government using the public opinion card more often. Although such changes in Japanese politics are expected, it is important to note that, as a political entity, the traditional political culture of Japan will not disappear overnight, and its indomitable vitality should not be underestimated (Benedict 1946). Bearing this background in mind, it becomes easier to foresee that— because the formulation and implementation of foreign policy have a certain degree of confidentiality, and because of Japan’s mastery of ‘‘secret foreign policy’’—a middle way of alternating between traditional informal mechanisms and transparent foreign policy will prevail.

(1972年田中角荣访华)

The above exposition of different routes or options for Japan’s foreign policy reflect the influence of both post Cold War changes in the international arena, and of changes in Japan’s domestic politics due to the increasing influence of public opinion. Although this transformation has not been as ‘‘revolutionary’’ as the previous two crossroads, it highlights a fundamental shift that is occurring. In other words, this formation of mainstream thinking in Japan’s foreign policy may be called the ‘‘silent revolution.’’

It should also be noted that the different choices referred to here are not always contradictory. For example, it is possible to become an economic power at the same time as becoming a military and political power. The purpose here is to emphasize the sequence or order of priority given to each of the policy options within Japan’s foreign policy. Understanding this alignment answers the so-called question of inclination. This middle-way approach is by no means a compromised position, but a balancing option between two extremes. It should also be emphasized that the old style of going to extremes in Japanese foreign policy has not totally vanished due to the appearance of this middle way. Instead, it may re-emerge from time to time and have an impact on specific policy makers.

For these reasons, this new policy direction is better called a ‘‘tilted middle way.’’ The dichotomy between Koizumi’s insistence on visiting Yasukuni Shrine and Fukuda’s willingness to forgo such visits in exchange for better Japan–China relations are specific examples of different inclinations in this middleway approach. Koizumi’s assertion that the ‘‘improving relationship with the USA will automatically improve Japan’s relations with China and Korea’’ is a reflection of the tendency toward datsu-a nyu-o; while Fukuda’s advocacy of ‘‘review[ing] the old while innovating the new’’ when he visited China and expressed his respect of Confucianism reflects an Ajia wa hitotsu tendency. Another important point is that this tilted middle-way approach in Japanese foreign policy has been nurtured over a long period of time. Its formation is a gradual process brought about through deliberation and debating. Although it began in the last century with the emergence of the post-Cold War era, it did not form into its present state until this century under the influence of Koizumi, Abe and Fukuda. Therefore, it is very important to understand this tilted middle way when studying Japanese foreign policy.