5 Policy Debates in Japan in the Background of Power Politics

The arguments concerning Japanese foreign policy reflect changes in Japan’s domestic politics, as well as the competitions among great powers. The mainstream Japanese foreign policies are moderate, but yet have some subtle intentions. From such policies we can see not only the conflicts between realism and idealism, but also how the country’s foreign policies have changed over time. For example, we ask this question when we are looking at current China–Japan relations: Is the China–Japan relationship simply a bilateral relationship, or an essential part in the global competition among great powers? The ChinaJapan relationship basically depends on Beijing and Tokyo; any other factors are hardly referred and considered.

Outside of the USA, Japan is the second most important external factor concerning the Taiwan issue. Furthermore, Japan and Taiwan are deeply related to each other for historical reasons. However, in the Japan–China–Taiwan triangle, China is a far more important character to Japan compared to Taiwan. Even though maintaining the disunity of the mainland and Taiwan is in Japan’s interest, Japan will not go straightforward and encourage going in such a direction.

Japan has given support to Taiwan’s independence movement, but when dealing with detailed problems, for example, trading negotiations, Japan does not have to compromise with Taiwan (Smith 2015). Here, we can refer to the Japan–Taiwan Fishery Agreement, which was signed in 2013. Japan and Taiwan had been negotiating for a long time without making any progress, because Japan knew that the mainland would not be happy if it compromised with Taiwan, and this was the reason why Japan held such a strong and tough attitude toward economic issues like fishery with Taiwan. In 2012, the dispute over the East China Sea became even more intense because of Tokyo’s ‘‘nationalizing’’ the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands.

China and Taiwan united and fought against Japan together on the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands issue, which was probably a situation that Japan wanted to see the least. People still remember how Japanese Coast Guard’s ships confronted China’s ocean surveillance ships, and the next day, they got into a water cannon fight with ships from Taiwan Coast Guard Administration.

If Japan did not try to control such a situation, the mainland and Taiwan would soon be officially standing against it on the islands issue. This was also an issue when Abe Shinzo returned to office. Under his leadership, the Japan–Taiwan Fishery Agreement was transformed from an economic issue to a strategic problem. Abe’s administration made it clear that Japan should try its best to achieve this agreement even if they had to make a concession to Taiwan. So, the agreement was immediately signed in 2013. In other words, Abe signed this agreement to get Japan out of the trap of the Diaoyu Islands situation.

From Japan’s perspective, signing the Japan–Taiwan Fishery Agreement was like killing two birds with one stone. One the one hand, it pacified the Taiwanese population. On the other hand, which was even more important, it broke the brief unity that mainland and Taiwan created during the island dispute. As a result, both Japan and Taiwan were winners, while China failed to unite with Taiwan over the defense of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands (Liu 2015, 297–306).

During the 2013 Conference on Taiwan in Beijing, a Chinese scholar acutely criticized Taiwan’s behavior of signing the fishery agreement, describing it as stabbing China in the back. He also questioned why Ma Yingjiu’s administration would consider betraying China.

From the Chinese perspective, the criticism was understandable. However, we will have to learn from Japan’s strategic thinking on its diplomacies. In other words, it made a small sacrifice (to Taiwan) to gain big benefit (broke mainland and Taiwan’s unity on the island dispute). Japan’s solution on this diplomatic issue is worth considering. In fact, this strategic thinking was also reflected when Japan changed its attitude on the ‘‘comfort women’’ issue and signed an agreement with Korea (Qian 2015). The agreement could never be reached without the strategic thinking of Japan, Korea, and the USA (Eilperin 2016).

(2015年,日本同意向韩国就“慰安妇”问题道歉,并赔偿受害者10亿日元。C)

It is easy to understand the old saying: ‘‘no permanent enemies, no permanent friends’’ when we look at the China–Japan relationship as part of the development of the Asia–Pacific region, especially with the competition among great powers (including the China–Japan–US trilateral relationship). From Japan’s third debate on foreign policy back in the 1990s to the change of the ruling party in 2009, the country’s public opinions had ‘‘drifted’’ several times. We could see the rise of a new opinion such as ‘‘drifting away from the USA and retaining our diplomatic independence.’’ From the independent foreign policy advocated by Hatoyama Yukio to the massive protests against Abe’s amendment intention in 2015 and the recent disagreements on issues like the Okinawa military base problem, a lot of different voices have been rising in Japan.

China should be aware of how deep and wide Japan’s domestic debates are and use the different intentions that appeared in those debates to achieve its own purpose. This method should also be considered when looking at the US–Japan relationship. For example, China should highlight the voices in the USA criticizing the various times Japan has sanitized its WWII history in its textbooks.

Of course, we should not overestimate Japan’s centrifugal force to America and ignore the rise of the conservative wing in Japan, as well as the possible negative effects of the changing global political climate. The tilted middle way direction of Japanese foreign policy can be understood as a collision between realism and idealism, as well as an evolution of Japan’s foreign policy. Recalling Japanese foreign policy since World War II, it is clear that policy toward the USA, with the Japan–US security treaty as a cornerstone, remains the top priority while foreign policy toward China can be regarded as coming second.

(1972年,日本时任首相田中角荣访华。)

Japan’s foreign policy has experienced significant changes from the Cold War to the creation of friendlier Sino-Japanese diplomatic relations marked by the 1972 rapprochement. Since the mid-1990s, calls have begun to be made for an end to the ‘‘1972 system’’ and start of a ‘‘normal relationship’’ (Inoguchi 2002; Wan 2006). With the collapse of the former Soviet Union, both China and Japan carried out a full range of adjustments toward each other through their foreign policies, which could be called ‘‘Power Politics’’. These diplomatic games reveal a greater focus on real interests than on ideological factors. Thus, consideration of national interest takes precedence when adjusting policy in order to deal with domestic and international situations.

This was obvious during Koizumi’s administration. From 2001 until 2006 when Koizumi stepped down, SinoJapanese relations shifted from relative stability to a phase characterized by low-level hostility. Scholars of course have different interpretations regarding the emergence of such a shift. Some scholars believe structural changes in the international environment caused the shift, while others argue that the main reason for such change was a surge in nationalist sentiment in Japan. Yet another interpretation holds that the rise of China triggered a sense of imbalance on the Japanese side. Each of these perceptions have some logic to their argument, the point is that both China and Japan have made mistakes in their policy toward each other.

5.1

Japan’s Misjudgment in the Koizumi Era

One of the features of games played by great powers is adjusting the old foreign policies according to the changing situations (both domestic and international), while the adjustments have to be based on national interests. The goal of such adjustments is emphasizing more interests and reducing the effects of idealism. This feature was really conspicuous during Koizumi’s term. From the mid-1990s to September 2006, the China–Japan relationship experienced a ‘‘relatively friendly to relatively hostile’’ transformation. Due to the lack of strategic thinking, Japanese diplomacy failed to manage the tendency of its ‘‘tilted way’’ foreign policy.

(2005年12月在马来西亚吉隆坡举行的第一次东亚共同体峰会,时任日本首相小泉纯一郎向中国总理借笔签署峰会宣言。)

This can be proved by comparing Japan with the USA regarding diplomatic policies on China. The Chinese scholar, Liu Weidong, summed up the following six different points:

(1) At the strategic level, Japan tends to fight, while the USA tends to guide;

(2) regarding security issues, Japan has both prevention and provocation, while the USA emphasizes cooperation and prevention;

(3) regarding trade issues, Japan pays more attention to economic opportunities, but lacks stability of its targets and meaning. In contrast, although the decisions of USA are often influenced by political factors, the connotation of its targets is stable;

(4) regarding Taiwan, the strategic importance of Taiwan is rising in Japan’s diplomacy, while such importance is gradually decreasing for the USA;

(5) regarding the Japan–US alliance, Japan uses it to contain China, while the USA attempts to use it to contain China and control Japan;

(6) on the ideological level, the attitude of Japan and the USA toward China are out of sync; when one rises and the other falls (Liu 2006).

Secondly, due to the lack of large-scale and long-term strategic thinking, Prime Minister Koizumi and his think tanks underestimated China’s determination on the Yasukuni Shrine issue, and the importance of China’s role in international affairs. Nevertheless, Japan’s refusal to listen to the criticisms of other countries on an internal matter was understandable, but its choice regarding the issue of Yasukuni Shrine put Japan in the position of having to be a loser. Japan’s position on this issue was even criticized by its allies. For example, Hyde, the chairman of the International Relations Committee of the US Senate, had written to Japan’s ambassador to the USA, in which he strongly criticized Koizumi visiting the Yasukuni Shrine. This criticism was not only from US politicians, but also from the US mainstream media, and even experts who had good relationships with Japan criticized Japan on this issue (Glosserman 2005; Ryback 2005).

For US foreign policy, the truth is obvious: you may act against China, but you should never reverse the verdict on the issue of World War II. Although in recent years the USA has lifted its restrictions on Japan’s constitutional issues, there is always a clear criticism from USA on the historical issues of Japan. For example, in September 2015 the Congressional Research Institute issued a lengthy report entitled ‘‘Japan–US relations problems faced by the Congress,’’ in which it describes the criticism from the USA on the issue of comfort women and Japan’s Yasukuni Shrine (Chanleu-Aversy et al. 2015, 7–8). From the diplomatic perspectives, the approaches taken by Prime Minister Koizumi in this context were particularly unwise.

(中国威胁论)

When Japan disregarded China’s views and continued the successive visits to Yasukuni Shrine, the relationship between Japan and China weakened. China shifted its attitude from vague into clear opposition regarding Japan’s desire to become a permanent member of the UN Security Council, which served as a good example to illustrate that Japan was not handling the Yasukuni issue well (Liu 2005a, b). Thirdly, there was a vicious circle between the Koizumi cabinet’s diplomatic policies toward China and its domestic conservative tendency; the interaction of which also largely limited the flexibility of Japan’s diplomacy. In other words, the upsurge of nationalism in Japan, made even more leaders adhere to the ‘‘do not listen to Beijing’s commands’’ and ignored whether the problem itself was right or wrong. The Yasukuni Shrine issue mentioned above was one such example. In turn, the leaders’ insistence also promoted the Japanese media’s criticism toward China, resulting in the sentiment of ‘‘boredom China’’ continuing to spread and exacerbated the confrontation between the people from the two countries (China Today 2005). Under such circumstances, it was also difficult for Japanese experts who had a deeper understanding of Japan–China relations to stand up and point out the errors to be corrected in Japan’s diplomatic directions.

Tensions were so high, that some politicians, officials, scholars, and entrepreneurs who did not agree with the government’s policy toward China were afraid to speak out on the issue, because they feared personal attacks and for their safety. This fear silenced a large number of people with dissident voices. This made it more difficult for Japan to push its diplomatic policy on China toward a more moderate path. This vicious interaction of course limited the possibilities14 Koizumi government had to carry out a pragmatic and flexible diplomacy on the issue of China.

5.2

China’s Misjudgment in the Koizumi era

Similar to Japan’s problem, China’s diplomacy during the Koizumi period is also worth considering. Firstly, regarding strategic priority issues, China has always followed its tradition placing its diplomacy with Japan in the global environment. In the Maoist period, Japan was considered to be part of the ‘‘Second World’’ between the USA, the Soviet Union and the ‘‘Third World,’’ which included China. Japan was considered a power that was able to collaborate within the triangular pattern of USA, Soviet Union, and China around Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. During the normalization of Sino-Japanese relations marked by Tanaka’s visit to China in 1972, although Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai had criticized Japan’s wrong historical view, China did not consider this a problem when it emphasized its global strategy consideration.

After 1978 when China entered a new era with Deng Xiaoping’s reformation and more open policies, China’s diplomacy was subject to its strategic goal of modernization, and its diplomatic policies to Japan were also paramount considerations (Li 2005). Chinese leaders criticized Japan’s wrongdoing on historical issues, including the textbook issue and Japanese leaders visits to the Yasukuni Shrine (for example, the incumbent, Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro), but they did not interfere with their own effort of improving relations with Japan to help promote the modernization of China’s strategic objectives (Zhao 2003).

However, during the period when Koizumi was incumbent, China’s foreign policy toward Japan seemed to reach an impasse and the bilateral relations became lopsided, which in turn compromised China’s core interests in other aspects (for example, on the possibility of creating a Japanese version of the ‘‘Taiwan Relations Act’’). That is, although China then held a remarkable strategy of ‘‘fight without breaking up,’’ regarding relations with Japan, it confined itself to the matter as they were and rarely put it in the Asia–Pacific global level, and therefore, China failed to widely make friends among Japanese elite circle and diplomatic channels were relatively limited.

Secondly, when making foreign policy, the country should be clear about its political influence. And, the country should apply its method of solving internal affairs and foreign affairs separately other than interchangeably. Even when the two countries are at war, the communication channels of the highest level should still be open. The USA and the Soviet Union still maintained the highest level of communication even during the peak of the Cold War. When dealing with complex international issues, one should make the best of the contradictions and mistakes on the other side, especially for the conflict between China and Japan (including the history issue and the Diaoyu Islands dispute), which was not a simple question on the technical level, but required more negotiation at the political strategic level. Therefore, China’s foreign policy during the Koizumi era does need further reflection (Zhao 2005). One successful example of political manipulation was the transformation of US–Japan relations. The USA transformed the deterioration of US–Japan relations, which was the result of ‘‘caveating Japan’’ in the 1980s, into the improved US–Japan relations under the revised guidance of US–Japan alliance policy in the latter 1980s (Zhao 2015).

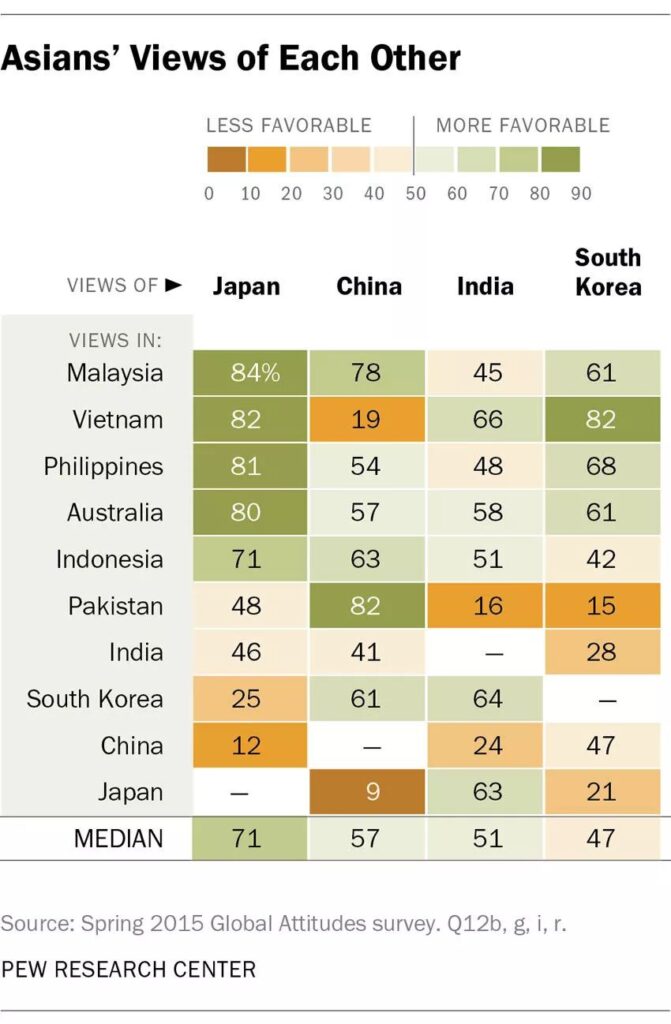

(2015年皮尤研究中心全球态度调查,亚洲各国对中国、日本的态度。)

Ironically, the improvement of Japan–US relations happened simultaneously with the deterioration of China– Japan relations, which proved that different diplomatic strategies do indeed play a pivotal role in the transformation of a country’s external relationships.

Thirdly, regarding the diplomacy with a specific foreign country, we should not only learn about the history of this country but should also grasp its current developments accurately. As described above, since the Meiji Restoration, Japan, under the policy of ‘‘datsu-a nyu-o (leave Asia, enter Europe)’’ and later developed militarism, brought great suffering to the people of Asia, especially China and the Korean Peninsula. However, we should also see that since end of World War II, Japan adopted a national policy of prioritizing economic development. Besides, its ‘‘peace constitution’’ also played a role in reducing the possibility of Japan’s foreign expansion. Inside Japan there is also a complex and arduous struggle on how to recognize the history issue. Japan’s actions in strengthening its military force do require caution, but such action is different in essence with the militarism Japan exhibited before.

Therefore, we need to do further research and emphasize a multi-angle study on such issues in Japan (Zhao 2015). Moreover, one should be clear about the mainstream thinking in Japanese diplomacy. In other words, one should pay special attention to Japan’s tendency moving towards its middle way diplomacy.

At the same time, relevant government departments should guide domestic nationalist sentiment to the positive development of China–Japan relations, in an insightful manner. To achieve this purpose, China should rely on its Japan experts as much as possible, such as the famous ’’Japan hand‘‘ Liao Chengzhi. China should also pay more attention to building relations with the new generation of Japanese politicians and should see their potential impact on determining which direction Japan is headed in their middle way diplomacy (Wu 2002). In particular, both the people and the government in China and Japan have carried out a profound reflection and rethinking on important China–Japan relations, which is of great importance to the Asia–Pacific region.

After Koizumi stepped down in 2006, the leaders of the two countries met and repeatedly expressed their determination to improve bilateral relations. Of course, the problem of their foreign policy mentioned above cannot be solved overnight and is also one of the many issues that influence the China–Japan relationship.

Although the summits between China and Japan were restored after the Koizumi government, there are still many other problems between China and Japan, for example, the disputes around the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, the issue of history (such as textbooks, Yasukuni Shrine), Japanese constitutional amendment, sending troops abroad. China’s determination to safeguard national sovereignty on the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, of course, is unshakable, but China should also pay special attention to some specific issues related to the overall situation on the operational level, such as how to maintain channels of communication with Japan, and crises provention and management. These problems are yet to be properly addressed by leaders in the future.

6 Future Directions of Japanese Foreign Policy

Although the first two policy debates (Meiji Restorarion and American occupation) represented orientational change with open debates among Japanese elites, the third political debate starting from the 1990s, however, lasted in a few years and in a less dramatic fashion. While one has to recognize that the debate itself was as vigorous as the first two, it was far less noticeable to the outside world, therefore might be called a silent revolution. However, the consensus of the ‘‘tilted middle way’’ had far-reaching significance in Japanese diplomacy.

A tilted middle way in Japanese foreign policy was a product of long debate and deliberation among Japanese society and political circles. The debate began in the end of the twentieth century and the framework started to take shape at the beginning of the twenty-first century under the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Prime Ministers Abe, Fukuda, and Aso and will continue for the foreseeable future with Abe’s election victory on October 22, 2017. Based on an analysis of this consensus and paying particular attention to the types of policy enacted by Abe and Fukuda and confirmed by Aso and Hatoyama, a few different preferences in terms of the inclination or tilt within the Japanese middle-way approach to foreign policy become apparent. First, Japan’s foreign policy will continue its post-war tradition of putting USA–Japan relations first. It is clear that Japanese leaders not only want to stress this alliance in order to ensure Japan’s security, but also intend to place more emphasis on common values such as democracy, which also coincides with trends developing through globalization.

At the same time, Japanese foreign policy will continue to express efforts to achieve the ‘‘fully independent sovereign state goals’’ as former Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro stressed (Nakanishi 2005, 10–17), placing more emphasis on national interests and independence (Green 2001). The two leading elements—security and common values related to the Japan–US alliance—will become the pillars behind Japan’s tilt, causing it to maintain its present strategic policy, with US–Japan alliance as the cornerstone, for the foreseeable future (Faiola 2006, A12). During the era of Abe and Obama, Japan’s diplomacy exhibited two different features: firstly, Japan paid effort to improve its relations with China and Korea. Secondly, Japan strengthened the Japan–US alliance by adhering to ‘‘active pacifism’’ so as to help the Obama administration in the pursuit of the ‘‘Pivot to Asia’’ strategy. President Donald Trump’s election makes US policy uncertain. It raises many questions about what form the US–Japan alliance will take.

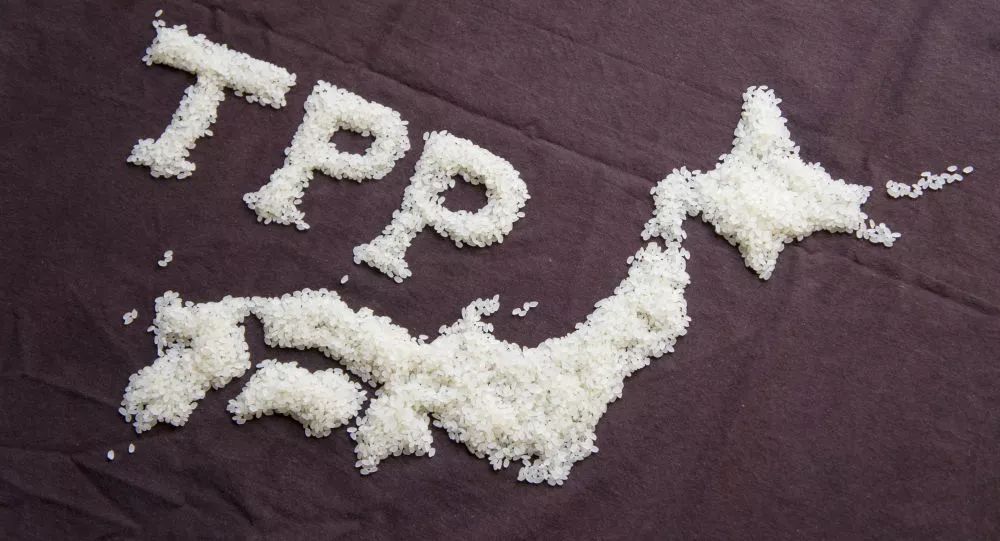

First, Japanese politicians are wondering to what degree President Trump will continue President Obama’s pivot to Asia policy. Japan is so concerned about Trump’s presidency, and Trump has already made decisions that have been issues of concern for Japan. The fact that Trump withdrew from TPP was a huge disappointment. With Trump’s presidency, Japan is reconsidering its foreign policy. Will Japan continue to rely solely on the USA or will Japan diversify its policy to not just rely on the USA, but to also improve relations with China?

Second, Japan will carefully handle relations with China. Although Tokyo is still concerned about the possible existence of threats similar to that of the ‘‘China threat theory,’’ it will focus more on strategic power transition in a macroscopic direction, showing more caution regarding issues such as Taiwan, which are central to China’s interests. This is also related to Japan’s own realistic interest, in that actions that may cause a worsening of relations from ‘‘politically cold and economically hot’’ (Beijing Review 2006, 19) to ‘‘politically cold and economically cool,’’ will harm the country’s fundamental interests (Hisaki 2006, 12–20). In order to avoid having to choose between Beijing and Washington, Tokyo will further strengthen its position calling for the development of a framework incorporating China, the USA, and Japan together. Needless to say, the China–Japan relationship is one of the key factors for China to improve relations between the surrounding countries and to keep the regional stability in the Asia– Pacific region. The China–Japan relationship is an ineluctable issue for China requiring innovative thinking from the strategic point of view.

From the perspective of its Japan policy, China should carefully study the development of political force and political thoughts in Japanese society so as to keep track of the diplomatic policy debate inside Japan and take advantage of the positive factors in China-Japan relations. In other words, China should find the common interests with Japan, from a strategic view in Asia–Pacific. After all, China and Japan have a longer history of peaceful coexistence, in which the two learned from each other.

Third, Japan will be more actively involved in the East Asia community’s economic development. It will also emphasize greater economic cooperation among groups such as the ASEAN-plus-three framework, and work to create a stronger strategy for value-driven regional integration by attempting to better integrate Australia, New Zealand and India into regional affairs. Such moves will allow Japan to both share in the regional leadership position with China, and also balance China’s ever-growing influence (Hiatt 2006, A21).

Fourth, Japanese political circles will continue to promote modifications to the country’s peace constitution in order to further improve Japan’s political and military power status. Japan will also continue its efforts to raise its status within international organizations, including the United Nations Security Council, making efforts toward both the USA and China in order to win support. Although Japan’s role in the North Korean nuclear problem is not the most important one, Japan will adopt a more positive attitude and position dealing with North Korea problem (Zhao 2006, 95–111).

Fifth, Japanese foreign policy will incorporate goals to strengthen Japan’s ‘‘soft power’’ to better help it attain its strategic goals. As the world’s third largest economy, Japan has the strength to carry out a more ‘‘soft power’’-oriented approach to foreign policy. Such a policy will not only rely on Japan’s economic diplomacy represented primarily through its use of ODA, but also incorporate an expanded use of its cultural diplomacy. Regarding Japanese culture, by emphasizing the exchange of young people, Japan continued to increase its output of Japanese values and culture, which served to strengthen its ‘‘soft power’’ diplomacy (Hagstrom 2015, 129–37). One such example of this policy is a program initiated in 2006 to support short visits and home-stays for Chinese secondary-school students to Japan. China–Japan youth exchanges were started as early as during Koizumi’s administration, pointing toward the goal of using people- to-people diplomacy building through cultural exchanges as a tool for creating better foreign relations and improving Japan’s international image abroad. Prime Minister Abe’s wife emphasized this point when visiting a middle school in Beijing (Feng 2006, 62–3). Thus, the use of cultural diplomacy in Japan’s ‘‘soft power’’ approach is likely to play a greater role in the future (Kondo 2005, 36–7).

As mentioned earlier, special attention needs to be given to the question of the tilt within the middle-way direction. Although this approach has become the preferred route of Japanese foreign policy, its inclination is heavily influenced by leaders (and their factions), particular policy areas, as well as pressing domestic and international political situations. These essential factors will be the basis of analysis and future research of Japan’s mainstream thinking and its possible changes. According to its consensus forming in the long debate, Japan balanced its diplomacy with other countries, or, in other words, Japan continued its international policy following the ‘‘tendentious’’ middle way. Although such tendentiousness varied in different periods, with different international environments and different internal political leadership, generally, Japan’s international policy returned to the ‘‘middle way,’’ which was the most beneficial to Japan’s national interests.